Out of Prison We Need Him Again

Out of Prison house & Out of Work:

Unemployment among formerly incarcerated people

Past Lucius Couloute and Daniel Kopf Tweet this

July 2018

Formerly incarcerated people need stable jobs for the same reasons every bit everyone else: to back up themselves and their loved ones, pursue life goals, and strengthen their communities. But how many formerly incarcerated people are able to observe work? Answering this fundamental question has historically been difficult, because the necessary national information weren't bachelor — that is, until at present.

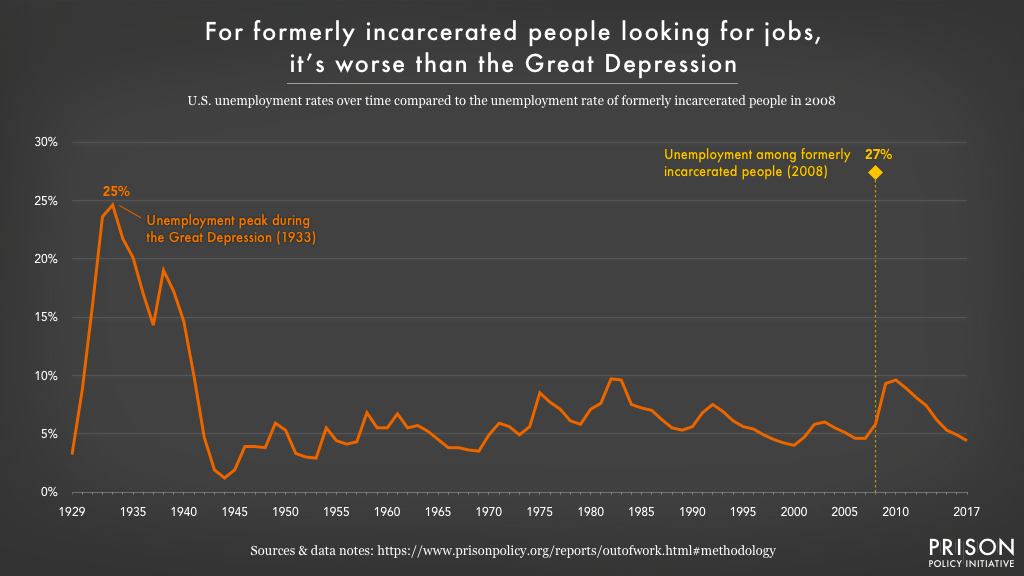

Using a nationally representative dataset, nosotros provide the starting time ever approximate of unemployment amidst the 5 million formerly incarcerated people living in the United States.1 Our analysis shows that formerly incarcerated people are unemployed at a rate of over 27% — higher than the total U.S. unemployment rate during whatever historical catamenia, including the Peachy Depression.

Our gauge of the unemployment rate establishes that formerly incarcerated people want to work, but face structural barriers to securing employment, particularly within the period immediately following release. For those who are Black or Hispanic — particularly women — status equally "formerly incarcerated" reduces their employment chances even more. This perpetual labor market place punishment creates a counterproductive organization of release and poverty, pain everyone involved: employers, the taxpayers, and certainly formerly incarcerated people looking to break the cycle.

Fortunately, as the recommendations presented in this report illustrate, there are policy solutions available that would create safer and more than equitable communities by addressing unemployment among formerly incarcerated people.

Unemployment amid formerly incarcerated people

Over 600,000 people make the difficult transition from prisons to the community each year2 and although there are many challenges involved in the transition, the roadblocks to securing a job have particularly astringent consequences. Employment helps formerly incarcerated people gain economical stability after release and reduces the likelihood that they return to prison,3 promoting greater public condom to the benefit of everyone. But despite the overwhelming benefits of employment, people who have been to prison are largely close out of the labor market.four

We observe that the unemployment charge per unit five for formerly incarcerated people is nearly five times higher than the unemployment rate for the general United States population, and substantially college than even the worst years of the Neat Depression.half dozen Although nosotros have long known that labor market outcomes for people who have been to prison house are poor, these results point to extensive economical exclusion that would certainly be the cause of great public business concern if they were mirrored in the general population.7

These inequalities persist even when decision-making for historic period. Among working-age individuals (25-44 in this dataset), the unemployment charge per unit for formerly incarcerated people was 27.3%, compared with merely 5.ii% unemployment for their general public peers. That such a large per centum of prime number working-age formerly incarcerated people are without jobs but wish to work suggests structural factors — similar discrimination — play an of import role in shaping job attainment.8

Prior research suggests that employers discriminate against those with criminal records, fifty-fifty if they claim non to. Although employers express willingness to hire people with criminal records, prove shows that having a tape reduces employer callback rates by l%.nine What employers say appears to contradict what they actually do when it comes to hiring decisions.10

Our analysis besides shows that formerly incarcerated people are more probable to be "active" in the labor market than the general public. Among 25-44 year old formerly incarcerated people, 93.3% are either employed or actively looking for work, compared to 83.8% among their full general population peers of similar ages.11 Though unemployment among formerly incarcerated people is v times higher than among the full general public, these results evidence that formerly incarcerated people want to piece of work.

Unemployment among this population is a thing of public will, policy, and practice, non differences in aspirations.

A closer expect: How employment varies by race and gender, time since release, and access to full-time work

Race and gender

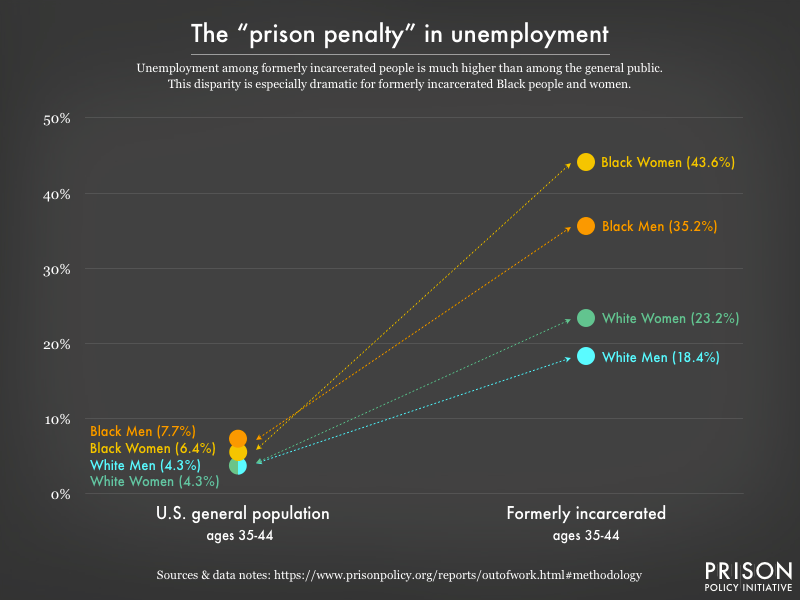

In the full general public, people of color tend to face up higher unemployment rates than whites, while men tend to have lower unemployment rates than women. The overrepresentation of people of colour and men among those who accept been to prison, then, could accept conceivably influenced the inequalities nosotros observed betwixt formerly incarcerated people and the general public.

After disaggregating by race and gender, however, we found that the unemployment charge per unit of every formerly incarcerated group remains higher than that of any comparable group in the general public. High unemployment among formerly incarcerated people is non simply explained by the overrepresentation of people of colour in the criminal justice system; it's the status of beingness formerly incarcerated that sets them apart.

But the story here is intersectional. Formerly incarcerated Black women in detail experience severe levels of unemployment, whereas white men experience the lowest. Overall, we meet working-age "prison penalties"12 that increment unemployment rates anywhere from 14 percentage points (for white men) to 37 percentage points (for Blackness women) when compared to their general population peers.13 Our findings mirror prior inquiry establishing that both race and gender shape the economic stability of criminalized people.xiv

| Unemployment rate general population | Unemployment rate formerly incarcerated | |

|---|---|---|

| Black women | 6.iv% | 43.6% |

| Black men | 7.7% | 35.2% |

| White women | four.3% | 23.ii% |

| White men | 4.3% | 18.4% |

Fourth dimension since release

We also find that unemployment is highest within the outset ii years of release, suggesting that pre- and post-release employment services are critical in guild to reduce recidivism and help incarcerated people quickly integrate back into society. Of those almost recently released from prison (that is, inside two years of the survey date), over 30% were unemployed. Unemployment rates were lower for those released within 2-3 years of the survey (21%), and people who had been out of prison for at least iv years reported the lowest rates of unemployment (simply under 14%). 15

| Year Released (Years since release at the time of the 2008 survey) | Unemployment rate |

|---|---|

| 2007-2008 (less than 2 years since release) | 31.6% |

| 2005-2006 (ii-3 years since release) | 21.1% |

| 2004 or before (4 or more years since release) | 13.6% |

The transition from prison back to the community is fraught with challenges; the search for employment is one of many tasks that tin derail successful reentry. In the period immediately post-obit release, formerly incarcerated people are probable to struggle to find housingxvi and achieve habit and mental wellness support.17 They besides face disproportionately loftier rates of death due to drug overdose, cardiovascular disease, homicide, and suicide within this crucial period.eighteen Taken together, these results make it easy to understand how various barriers to reentry operate as an interconnected system to increment inequality.

Access to full-time work

When formerly incarcerated people do land jobs, they are often the near insecure and lowest-paying positions.19 According to an analysis of IRS data by the Brookings Establishment,20 the majority of employed people recently released from prison receive an income that puts them well below the poverty line.21

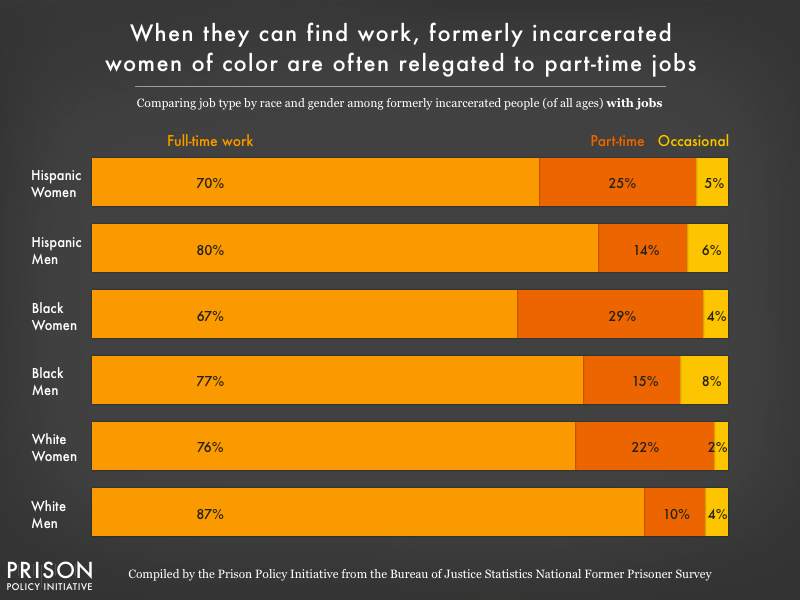

Our information suggests that, in combination with a criminal tape, race and gender play a significant role in shaping who gets access to good jobs and livable incomes. Almost all employed formerly incarcerated white men (the grouping almost likely to be employed) piece of work in full-time positions, whereas Blackness women (the grouping least probable to be employed) are overrepresented in office-time and occasional jobs (come across figure 3).

Though Black women in the full general public tend to have college rates of full-time work than their Hispanic or white peers, low rates of total-time work among formerly incarcerated Black women illustrates that gender and race operate together in the context of reentry.22

Conclusion

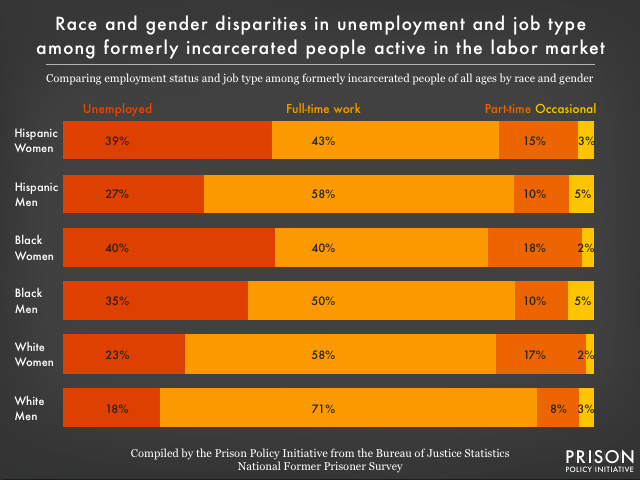

One of the primary concerns for people being released from prison is finding a job. But as our assay illustrates, formerly incarcerated people are virtually 5 times more than probable than the full general public to be unemployed, and many who are employed remain relegated to the near insecure jobs. Our analysis also shows that formerly incarcerated people of color and women face the worst labor marketplace disadvantages despite being more than probable to be looking for jobs (Encounter Table three).

Exclusionary policies and practices — not private-level failings of criminalized people — are responsible for these labor market inequalities. Fortunately, research shows that those with prior criminal justice organization contact desire to piece of work and that hiring them can benefit both employers and the general public:

- Research based on i.three million United States war machine enlistees shows that those with criminal records were promoted more quickly and to higher ranks than other enlistees, and had the aforementioned attrition rates due to poor performance as their peers without records. 23

- A study of task performance among call center employees establish that individuals with criminal records had longer tenure and were less likely to quit than those without records.24

- One longitudinal report out of Johns Hopkins Hospital establish that subsequently "banning the box" on initial applications and making hiring decisions based on merit and the relevance of prior convictions to particular jobs, hired applicants with criminal records exhibited a lower turnover charge per unit than those with no records.25

The evidence illustrates that broad stereotypes nearly people with criminal records have no real-world basis. But convincing employers that people with criminal records are good workers is not enough. Improving the wellbeing of formerly incarcerated people — and increasing equity in all communities — will require concerted policy efforts that address the underlying structural sources of inequality shaping the lives of criminalized people across the United States.

Recommendations

There are promising policy choices available to lawmakers at each level of authorities that would aid formerly incarcerated people proceeds employment and increase public safety:

- Issue a temporary basic income upon release: Providing short-term fiscal stability for formerly incarcerated people would operate every bit an investment, helping to ease reintegration and provide public rubber and recidivism reduction benefits that would result in long-term cost savings.32

- Implement automated record expungement procedures: A prison sentence should not be a perpetual penalisation. Having an automated machinery for criminal record expungement that takes into account the offense type and length of time since sentencing would, in the near term, help formerly incarcerated people succeed and would, in the long term, promote public safety. 31

- Make bond insurance29 and tax benefitsthirty for employers widely bachelor: Some governmental bodies offer insurance and tax incentives for employers who hire people with criminal records, protecting against real or perceived risks of loss. Increasing the availability of such programs would provide hesitant employers with added fiscal security.

- Ban blanketed employer bigotry:26 Criminal records are not expert proxies for employability. Additionally, because of racially disproportionate incarceration rates, organizations who discriminate against people with criminal records may likewise be contributing to racial bigotry and are therefore subject area to litigation under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.27

- Enact occupational licensing reform: Numerous occupations require prospective workers to obtain task-related state licenses. Unfortunately, acquiring such licenses often involves passing a criminal background bank check. States should reform their licensing practices so as to eliminate the automatic rejection of people with felony convictions.28

Appendix

Employment outcomes for formerly incarcerated people vary widely by race and gender. In the chart and tabular array beneath, we explore these disparities in richer particular:

The unemployment rate in all demographic groups is different from the joblessness rate. Joblessness includes anyone who does not have a job, whether they are looking for i or not, and was, prior to our analysis, the only measurement of formerly incarcerated people's labor market status. Unemployment, which is typically used to mensurate the economic well-beingness of the general U.South. population, includes but those people who want to work but can't find a job. The table below provides both figures.

| Race/ethnicity | Gender | Jobless charge per unit | Unemployment rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hispanic | Women | 51.39% | 39.42% |

| Men | 33.14% | 26.55% | |

| Blackness | Women | 51.37% | forty.00% |

| Men | forty.96% | 34.96% | |

| White | Women | 38.17% | 23.ten% |

| Men | 27.17% | 18.31% |

Methodology

This report calculating an unemployment charge per unit for formerly incarcerated people is based on our analysis of a little-known and little-used government survey, the National Onetime Prisoner Survey, conducted in 2008. The survey was a production of the Prison Rape Elimination Human activity, and is therefore primarily virtually sexual attack and rape behind bars, just it besides contains some very useful information on employment.

Because this survey contains such sensitive and personal data, the raw data was not available publicly on the net. Instead, information technology is kept in a secure data enclave in the basement of the Academy of Michigan Found for Social Research. Access to the data required the approval of an independent Institutional Review Board, the approval of the Bureau of Justice Statistics, and required us to access the data nether close supervision. The practicalities of having to travel across the state in social club to query a figurer database limited the corporeality of time that we could spend with the data, and other rules restricted how much information we could bring with usa. For these reasons, at that place are two tables (Table 1 and Tabular array 2) where, if nosotros had the benefit of retrospect or the resource for a render trip to the enclave, we would have collected some more than nuanced data to make comparisons by race/ethnicity, gender, and historic period even more complete. Even so, to the all-time of our knowledge, the analysis in this written report is the but i of its kind to date.

Why nosotros examined unemployment

Although the employment condition of formerly incarcerated people is non a new field of study, this written report extends upon previous research by constructing an unemployment rate for formerly incarcerated people that is like to what is typically accepted by economists: those who were non employed at the time of the survey only were bachelor and actively looking for a chore, divided by the total number of people in the labor force (Note: the Bureau of Labor Statistics considers jobless people who have looked for work in the past 4 weeks as part of the labor force. The National Former Prisoner Survey does not stipulate four weeks and instead asked respondents if they were currently looking for piece of work).

Traditionally, researchers have used joblessness every bit a mensurate of mail-imprisonment labor marketplace success, a measurement that includes anyone who does non have a job, whether they are looking for 1 or not. Calculating the unemployment rate allows policymakers, advocates, and the general public to directly compare the labor market place exclusion of formerly incarcerated people to that of the rest of the Usa.

As we have done in the by,33 comparisons between the formerly incarcerated and general U.S. populations were disaggregated past factors such every bit age, race, and gender in order to account for the established relationships betwixt those factors and labor market outcomes. In this style, we provide rough controls that help us examine comparable populations.

Data sources

We used the Bureau of Justice Statistics' National Former Prisoner Survey (NFPS) as our primary information source. This survey began in Jan 2008 and ended in October 2008, and was derived from the Prison Rape Elimination Act of 2003, which mandated that the Bureau of Justice Statistics investigate sexual victimization among formerly incarcerated people.

The NFPS dataset includes 17,738 adult respondents who were formerly incarcerated in state prisons and under parole supervision at the fourth dimension of the survey. Individual respondents were randomly selected from a random sample of over 250 parole offices beyond the United States.

It is important to annotation that because this survey was given to people on parole, it is not a perfect tool to measure the employment experiences of all formerly incarcerated people. Some incarcerated people are released without supervision and their ability to achieve employment may be different than those on parole. Previous research suggests, all the same, that parole officers have a minimal effect on mail-release employment, far outweighed by the outcome of having a criminal tape. In a 2008 Urban Institute study, but xx% of formerly incarcerated men institute their parole officers helpful in finding a job when surveyed two months after release; after eight months, only 13% idea their parole officers were helpful. Yet seventy% of the men believed that their criminal record had negatively afflicted their job search.34 A more than recent report finds that for people on parole in Florida, supervision did not have a pregnant consequence on employment outcomes, although it had a positive effect for those under supervision as part of a dissever sentence.35 Time to come inquiry should more closely examine the effect of supervision on employment.

Nosotros drew upon specific NFPS survey questions for this report:

- A2. Are you lot of Hispanic or Latino origin?

- A3. Which of these categories describes your race?

- B3. In what month and year were y'all released from prison?

- C1. Are you male, female, or transgendered?36

- F18. Exercise you currently accept a job?

- F18a. Is it total-time, part-time, or occasional piece of work?

- F18b. Are yous looking for work?

Comparable general United States population information was gathered from the Agency of Labor Statistics Current Population Survey.

Historical U.S. unemployment data for Figure 1 comes from two sources:

- For 1931-32, 1934, 1936-39, 1941-44, and 1946:

Stanley Lebergott. 1957. Almanac Estimates of Unemployment in the United States, 1900-1954. The Measurement and Behavior of Unemployment (National Agency of Economic Inquiry), 211-242. Note that this source includes people historic period 14 and over. - For 1933, 1935, 1940, 1945, and 1947-2017:

Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey. 2018. Produced using the Bureau of Labor Statistics data tool "Databases, Tables & Calculators by Subject." This source includes people age 14 and over until 1945; starting in 1947 information technology includes people age 16 and over.

About the Prison house Policy Initiative

The non-profit, non-partisan Prison Policy Initiative was founded in 2001 to betrayal the broader damage of mass criminalization and spark advocacy campaigns to create a more just society. The arrangement is known for its visual breakdown of mass incarceration in the U.S., as well as its information-rich analyses of how states vary in their apply of penalty. The Prison Policy Initiative's research is designed to reshape debates around mass incarceration by offer the "big film" view of critical policy issues, such as probation and parole, women's incarceration, and youth confinement.

The Prison Policy Initiative also works to shed light on the economical hardships faced past justice-involved people and their families, often exacerbated by correctional policies and practice. Past reports have shown that people in prison and people held pretrial in jail start out with lower incomes even earlier abort, earn very low wages working in prison, yet are charged exorbitant fees for phone calls, electronic messages, and "release cards" when they become out.

About the authors

Lucius Couloute is a Policy Annotator with the Prison house Policy Initiative and a PhD candidate in Folklore at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, his dissertation examines both the structural and cultural dynamics of reentry systems. His previous work with the Prison Policy Initiative examines reentry, solitary confinement, and the elimination of in-person jail visits across the country.

Daniel Kopf is an economics reporter for Quartz and and a former data scientist who has been function of our network of volunteers since Feb 2015. He has previously written about coin bail and has co-authored several exciting statistical reports with the Prison house Policy Initiative: Prisons of Poverty : Uncovering the pre-incarceration incomes of the imprisoned, Separation by Bars and Miles: Visitation in land prisons, and The Racial Geography of Mass Incarceration. Dan has a Main'due south degree in Economic science from the London School of Economic science. He is @dkopf on Twitter.

Acknowledgements

This study benefitted from the expertise and input of many individuals. The authors are specially indebted to Alma Castro for IRB assistance, Allen Beck for his insight into the NFPS, the ICPSR staff for their information retrieval support, Elydah Joyce for the illustrations, our Prison house Policy Initiative colleagues, and the National Employment Law Project for their helpful comments.

This report was supported by a generous grant from the Public Welfare Foundation and past our individual donors, who give us the resources and the flexibility to speedily turn our insights into new movement resource.

Footnotes

Source: https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/outofwork.html

Post a Comment for "Out of Prison We Need Him Again"